La educación colonizadora y el protagonismo de la historia

Los estragos de la colonia y la colonialidad

Victimización y resistencia

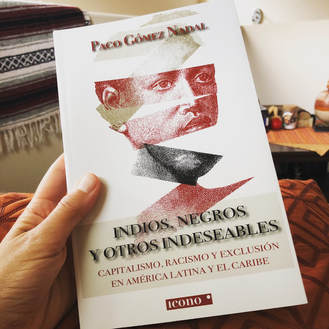

El dominio del cuerpo “indeseable”

El eco en el cuerpo

Reclaiming indigeniety

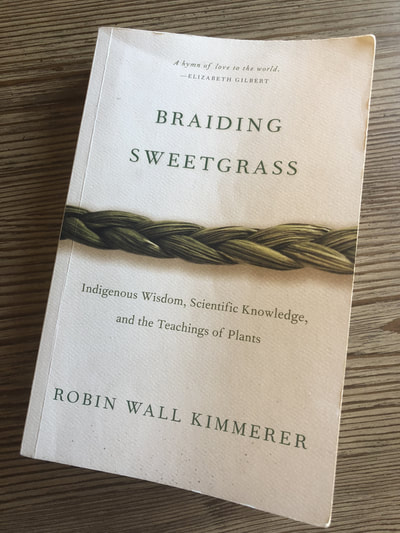

By expanding my understanding of listening and relational presence while remembering how to establish a reciprocal relationship to land and more-than-human nature. This process has been supported by the writings of Robin Wall Kimmerer, specifically her book Braiding Sweetgrass. The wisdom that she carries has inspired me to create a daily ritual of gratitude, look for concrete ways to give back to Mother Earth, and spend more time in the company of (and dancing with) my non-human brothers and sisters. Honoring African rootsThe Latin American vernacular dances that I grew up dancing are grounded deeply in their African roots. By embracing characteristics of the African aesthetic (e.g. body isolations, polyrhythms, dancing closer to the floor) and expanding my current practice to include rhythmic-based improvisation, I aim to decolonize my experience through embodiment.

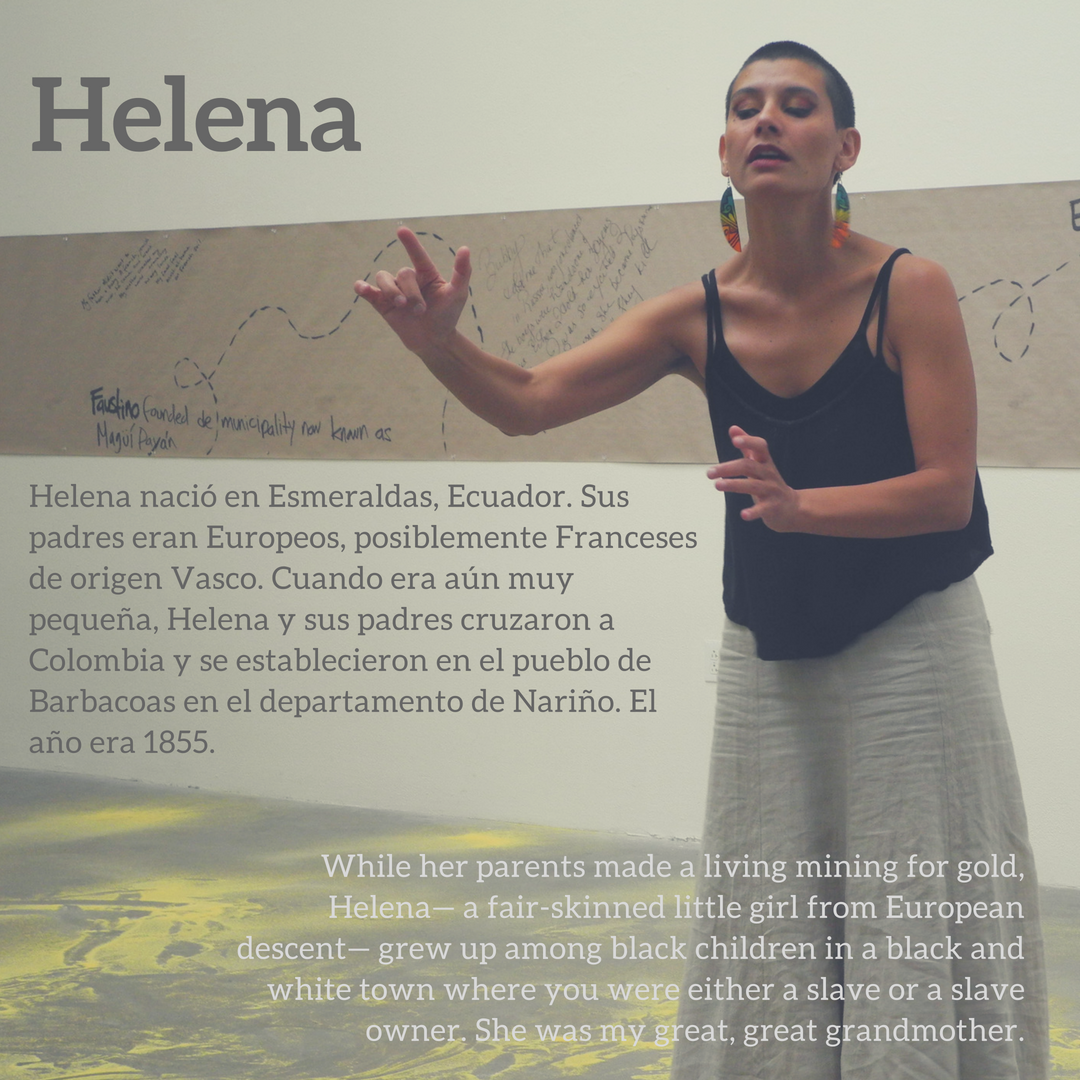

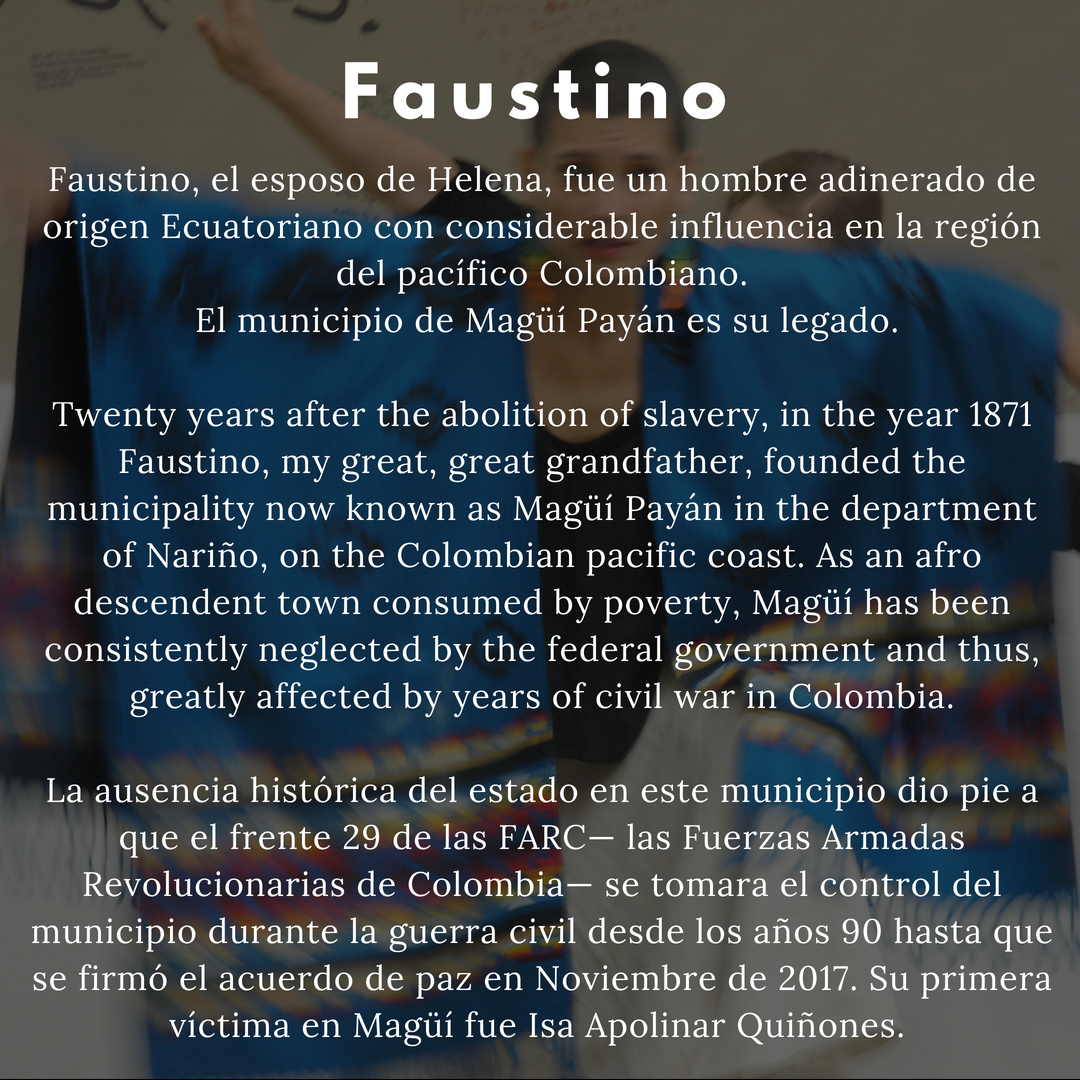

Making storiesWhile in residence at SFAI I began to use storymaking as a way to reclaim my lost family lineage. I wrote three short (mostly) fictional stories drawing from memories, stories told and written by family members, historical facts, news articles and documentaries. These have become a space for me to wrestle with the complexities of mi mestizaje and confront the colonial narrative in my family’s past and present in an effort to create an alternative one in the future.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed